So much of what we experience in life is profoundly personal. Not because it should be hidden from others, but because even if we wanted to share these experiences, we often don’t have the right words. We can’t muster the right combination from our vocabulary to have them completely resonate with others. Communication through language, both verbal and written, has a natural limit to how far it can take us in understanding one another.

A neat piece of anecdotal evidence that highlights how to come to this conclusion is looking at existing words in other languages that have no direct English translation. Here are a few examples.

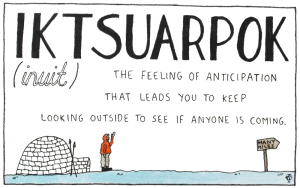

Iktsuarpok (Inuit)

The feeling of anticipation when you’re waiting for someone to show up at your house and you keep going outside to see if they’re there yet.

Glas wen (Welsh)

A smile that is insincere or mocking. Literal translation is a blue smile.

Kummerspeck (German)

Excess weight gained from emotional overeating. Literal translation is grief bacon.

Yuputka (Ulwa)

A word made for walking in the woods at night, it’s the phantom sensation of something crawling on your skin.

Toska (Russian)

Vladmir Nabokov describes it best: “No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody or something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom.”

These words reach out into a common core experience and crystalize that experience into a few syllables. The fact that they don’t exist for English speakers paints a good picture of how inadequate a single language is as a means of communicating meaning.

Worse yet, many of the words we take for granted as broadly defined can have varying interpretations based on past experience. Or, we rely on parties with commercial interests to define them for us and naively use the definition to create faux meaning.

Take a word like “love”.

I say the word “Love” and it comes out of my mouth and you hear the word. You process that word by recalling all your past experiences of love, or lack of love, and you interpret it. However, those experiences of love can differ significantly from mine.

Now imagine entire conversations at the average talking pace 153 words per minute. Much of whether you fully interpret meaning from what people say relies on your shared past experience.

In instances where we don’t share common interpretations for the words we speak, we are forced to abstract the experience and, through some kind of trial and error, explain the experience to someone. We do this until the individual has some kind of pattern recognition and says AHA Yes! I understand this experience.

This is easy for non-complex subjects but becomes tricky at higher levels of complexity.

There are three elements at play here when we attempt to understand one another. The Knower (the person describing the object), the object of understanding (this is the situation, or message being communicated) and the perceiver (the person interpreting the object based on their frame of reference).

Compatibility Effect

There are certain people you meet in your life that somehow break through the natural ceilings created by language. When you meet these people, it feels like they are on the same wavelength. You gel with them and you can’t help from having repeated “ya!!” moments with them.

This is compatibility effect. It’s as if the culmination of all their past experiences are so similar to yours, or perhaps the object they seek so similar to the object you seek that you can have unfiltered, spontaneous conversations about hugely abstract concepts and ideas.

Broken down: When the object of understanding is similarly interpreted with relative ease, the knower and the perceiver are in a state of compatibility.

This is not to say the person sees the word the same way you do. They could be a musician, and you an engineer. However your share a common foundation and have just chosen different paths. In fact, finding compatibility in individuals with vastly different lifestyles is sometimes the most enlightening.

When you find people like this, don’t let them go. Learn more about how things works through conversation, art, and story. To explain this simply:

Pretend for a second you are a simple computer program written to go out into the world and experience everything possible. Your greatest limiter would be the time it takes to form those experiences. However consider for a second you meet a program written in the same language. A program that had similar but varied sets of experience from yours with a common base programming. Then you could sync up and engage on objects of understanding to shift your frame of reference and see those objects in a new way (ie. increase the rate at which you form new experiences).

Finding compatibility.

A good way to find compatibility is through a tool often used in conflict resolution and counseling called Active Listening.

It requires that the listener (perceiver) repeat what they hear to the speaker (knower) — re-stating or paraphrasing what they have heard in their words, to verify what they have heard and confirm understanding of both parties.

Working together to find common ground on the object of understanding will greatly help you expand your frame of reference, empathy, or what I sometimes call the lens through which you perceive the knower(s).

Find compatibility and learn from these people. It’s the only way I know of to take BIG JUMPS in learning about the nature of things.